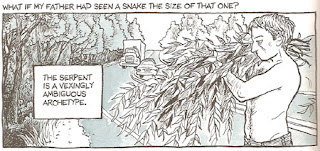

The graphic novel set-up, which took Bechdel over 8 years to create (watch an interview about her process here), intermingles classic literature with Bechdel's story, a style that makes sense in the context of her life and relationships. Her father was an English teacher, and she an avid English student; the inclusion of the stories of Daedalus and Icarus, along with multiple references to the works of James Joyce, serve to create a massive metaphor that extends throughout the entire novel. Daedalus is the Cretan inventor who constructed the Minoan labyrinth, the home of the Minotaur; he was later imprisoned by the King of Minos to keep the secrets of the labyrinth safe. Daedalus then built two sets of wings for himself and his son, Icarus, so they could escape. The wings were sealed with wax, which meant that both father and son had to fly steady and even to keep the sun from melting the way or the waves of the ocean from destroying the feathers. Icarus, however, got cocky, flew too high, and the wax melted -- Icarus plummeted to his death. Eventually, James Joyce came around and, inspired by this tale, named his main character in both Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses Stephen Daedalus, drawing a not-so-subtle parallel between the genius of the inventor and the genius of Joyce's autobiographical character.

However, the graphic novel's comparisons sometimes seem forced. Bechdel will occasionally use page after page of explanation in order to get this metaphor to make sense, and even then it still might not make sense. At various points in the novel, both she and her father are supposed to be both Daedalus and Icarus -- if that's not a strained comparison, I'm not sure what is. I get her point: both she and her father are human, they both have flaws, and they both have reached high for their arts and suffered setbacks. But the method she employs to bring this metaphor to life takes too much effort to put back together. It fits what she wants, I supposed, but it doesn't read well.

The only time it makes any sense (any easy sense, perhaps) is on the last page of the novel.

So, potential

It's not much of a spoiler, since I'm not going to explain how the novel gets to its ending, but still: just in case.The last page talks about how when Alison Bechdel really needed her father to be there, he was -- the line is something like "he was there to catch me when I flew," but I don't have the book in front of me as I write. Here, the comparisons between Daedalus and Icarus make sense -- Bechdel is both in that she is ambitious and she is trying, and she is Icarus in that she is overly confident in where she's going when in reality she has no idea what will happen. Her father is Icarus in that he is disconnected, he is pushing the limits of his life too far, and he is cruel in his own way, and he is Daedalus in that he is there for her without meaning to be, he is smart and clever and inventive and hiding, and he is her father. He let her explore but stayed her protector, and he improves on Daedalus in that he stays to catch her instead of letting her fall. Here, once, the metaphor makes perfect, unadulterated sense. Too bad it's on the very last page.

|

| It just doesn't make sense in the context of the rest of the graphic novel. Hm... |

Their relationship seems somewhat abusive at times, as her father is a tough parent with high behavior and aesthetic standards. The family as a whole is somewhat disjointed, each in their own little space, which adds to the distant feelings the novel generates. Bechdel herself deals with a lot of issues within the novel, a lot of issues that most of the time don't seem to have anything to do with her father. She spends time discussing getting her period and her college experiences, how she figured out she was a lesbian, how she conquered her OCD. And none of these seem to have any real connection with her father -- both on the page as Bechdel presents them and as I try to draw inferences as I read the book.

So overall, I just don't understand why Bechdel wrote this novel. It's fragmented -- it's about memory, not about creating a cohesive story, which is unusual as a writing style but not unusual as a thought style. In fact, that's how much of human thought is: fragmented, pulling up memories as they connect to current experiences. So I understand how the events of the novel are put together, I just don't understand why. Bechdel admits in the book that she doesn't experience much grief over her father's death, which would be my first thought for motivation in writing it. I know that many nonfiction pieces don't have overarching themes or messages -- part of reporting life as it happens instead of artificially infusing it with meaning -- but there is still a reason for something to be written. She could be writing to find closure; she struggles with the possibility that her father might have committed suicide, as in the prevailing opinion of most of her family. But I have to say, there are journals for those types of struggles, and I would imagine there is little reason for that to be made public.

Ultimately, the best idea I can come up with is that she's writing to make sense of a life in which a major player dies, to make sense of her life in relation to her father's death. Maybe there isn't something important Bechdel is trying to do here, maybe she's just documenting the overlap of two confused, struggling lives.

Perhaps I need to read it again. Or save it and read it again someday far in the future after my own father dies (though he is neither homosexual nor distant, so there won't be a ton of similarity). Or maybe I just don't like this book.

No comments:

Post a Comment